Boeing sticks to safety strategy, with new audits, officers and data

Published in Business News

As Boeing attempts to rebuild its reputation among safety regulators and the flying public, the company’s safety office is sticking to a strategy put in place after two 737 Max crashes six years ago.

In its fourth annual safety report since the deadly Max crashes, Boeing laid out a multipronged safety plan focused on strengthening safety culture among employees, incorporating risk management into its practices, and collaborating with airlines and regulators.

Though Boeing has outlined its plan several times in the years since the crash, and again since a January 2024 panel blowout on an Alaska Airlines flight, some regulators, lawmakers and employees are skeptical they will see lasting changes at the company. A recent company survey found Boeing employees don’t trust senior leadership and don’t feel their contributions are recognized or valued. On its factory floors, some employees worry the company prioritizes production rates over safety.

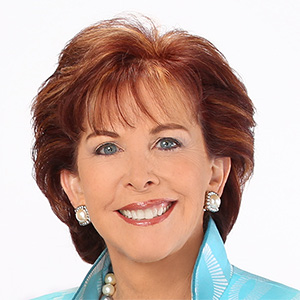

But Boeing is making progress on those long-term initiatives it sought after the two fatal crashes in 2018 and 2019, said Don Ruhmann, who took over as Boeing’s chief safety officer in March. Ruhmann replaced Mike Delaney, the first to hold the position since Boeing created it.

In the past year, Boeing hired a human factors chief engineer, and brought on a new executive to lead the team tasked with auditing safety and quality within the company. It added a new lab — called Safety and Airworthiness Focused Engineering, or SAFE — to help employees who are developing documents used in the certification of airplane parts.

In January, Boeing added “no-notification” audits, at five commercial sites. Compared to scheduled audits that are usually a long-term effort with several people involved, these audits start with less than 24-hours notice, involve just one or two people and target a specific product.

Since the January 2024 panel blowout, Boeing has increased its focus on tracking tools, simplifying work instructions and reducing “traveled work” — unfinished jobs completed out of the normal production sequence. That can disrupt other tasks on the plane, creating additional safety risks.

Doug Ackerman, Boeing’s vice president of quality, said at a news briefing Tuesday that traveled work has been reduced on every program, including fewer unfinished jobs moving between stations in the factory and fewer incomplete tasks remaining when planes roll out of the warehouse.

Ruhmann is optimistic Boeing’s safety plan is working as the company intended. The company’s “investments” have positioned it “very well to affect a different outcome on safety,” he told reporters Tuesday.

Employees speaking up

In the year since the Alaska Airlines panel incident, Boeing saw a 220% increase in reports filed through Speak Up, its internal tool for employees to share safety concerns and feedback.

Much of the spike is caused by the Alaska Airlines disaster, which occurred on Jan. 5, 2024, Ruhmann said. But, in the first four months of this year, the volume of reports is still roughly triple the same time period in 2023, he continued.

The Speak Up system allows employees to anonymously report concerns, but workers have criticized the tool and the company for failing to protect employees’ identities and making it difficult to follow the outcome of their complaint.

An audit of Boeing’s processes and systems last year, led by a Federal Aviation Administration-convened expert panel, found Boeing employees fear retaliation if they speak up and lack confidence that changes would be made if they do make suggestions.

In response to employee concerns, Boeing spent the last year strengthening its Speak Up system, Ruhmann said. It rolled out confidentiality training for those people reviewing complaints and changed the protocol so an employee’s direct manager would never respond to a complaint the worker had filed.

It also updated the employee dashboard, so workers can track the status of their report, as well as see overall data on the volume and outcome of other complaints.

Boeing’s engineering union — the Society of Professional Engineering Employees in Aerospace, or SPEEA — has long been working to set up a reporting channel that allows employees to share safety concerns with regulators, mirroring a system that is in place at some airlines. But the union has accused Boeing of dragging its feet, according to Scott Hamilton, an aerospace analyst with Leeham News, who was also at Tuesday’s news briefing.

Ruhmann said Boeing and the union are having “ongoing discussions … with the intent of deploying a program that’s consistent with the industry best practices.”

FAA oversight

In October, the Department of Transportation’s inspector general found the FAA had a “failing system” for its oversight of the largest U.S. airplane manufacturer.

One program, in particular, was not working as it should, the inspector general claimed in a scathing report that reviewed years of interactions between Boeing and the FAA. That program — called Organization Designation Authorization, or ODA — allows Boeing employees to certify some tasks on behalf of the FAA, in an effort to make the process more efficient and conserve government resources.

The ODA program has long been criticized for allowing Boeing too much control in its factories, and for failing to ensure the Boeing employees working on behalf of the FAA are protected from interference or retaliation.

But the program has started to see improvements, Boeing said in its safety report.

A 2024 Boeing-led survey of employees who performed certification tasks on behalf of the FAA found roughly 9% of respondents said they had experienced perceived interference in 2024, down from 12% a year earlier and 14% in 2022.

Among suppliers, no survey respondents said they experienced interference last year, compared to 3.4% a year earlier.

Boeing changed the structure of the ODA program last year so employees working on behalf of the FAA are independently reporting to engineering leaders, a change from a structure that had a variety of reporting paths.

It also added more employees to the ODA unit and improved its “ODA pipeline” to address retirements. In 2022, Boeing added an ombudsperson to the program, to act as a neutral third-party to address employee concerns.

After the Max crashes and quality issues with Boeing’s Dreamliner, the FAA retained its authority to issue airworthiness certificates for the 737 and 787, rather than allowing the manufacturer to perform the final inspection itself.

Learning from the past

This year, Boeing continued several safety initiatives underway since it started its annual safety report three years ago.

It continued to bring experts to airline customers and regulators, sending pilots, maintenance and engineering staff to the airlines who are set to receive a new plane to mitigate any concerns before the aircraft are delivered.

Building on a platform launched in 2023, Boeing publicly posted last year a timeline of past aviation accidents and technological advancements, illustrating lessons learned from the past and how they influence decisions today.

And, it expanded its use of machine learning and algorithms to help predict risk areas before they pose a safety concern.

“I’m building on the capabilities Boeing has built over the last 10-plus years,” Chris Norby, executive director of Aerospace Safety Analytics, said at the news briefing Tuesday.

As an example of using machine learning to analyze data and improve operations, Norby pointed to the use of surveillance-broadcast data on Boeing’s planes to analyze trends and risks when landing.

Because that system only collects information every four to six seconds, Boeing designed an algorithm to fill in the blanks. The end result was nearly as precise as a sensor on the airplane could be, Norby said.

That data will help Boeing proactively monitor “touchdown performance” across its fleet and the world, Norby said, reducing risks of runway overruns.

©2025 The Seattle Times. Visit seattletimes.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments