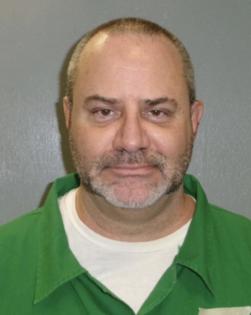

South Carolina firing squad 'intended to miss,' cause inmate 'extreme suffering,' lawsuit says

Published in News & Features

COLUMBIA, S.C. — When the three executioners fired their high-powered rifles at him, Mikal Mahdi, who was sentenced to death for the execution-style murder of an Orangeburg police officer, yelled. Over the next 80 seconds he moaned twice more before drawing his final, gasping breath.

Protocol required the executioners to aim for Mahdi’s heart. But despite three shots, an autopsy revealed only partial damage to his heart and just two bullet entry wounds. This is proof, say lawyers for a man facing execution Friday, that only two bullets were fired and both missed their mark.

While they offer no motive, lawyers for Stephen Stanko, set to die by lethal injection on Friday, June 13, have argued in a federal lawsuit that this is the only conclusion based on their review of Mahdi’s autopsy and multiple experts who opined that it would be nearly impossible for trained marksmen to accidentally miss a target at such close range. As a result, Stanko’s lawyers argue Mahdi died an agonizing death of blood loss inside of the state death chamber.

The “available evidence reflects that those responsible for conducting the Mahdi firing squad intended to miss the direct target and... avoid an instantaneous death to instead cause Mahdi’s extreme suffering,” Stanko’s lawyers write.

The South Carolina Department of Corrections has strongly refuted that anything went awry.

In a sworn affidavit, the department’s interim director, Joel Anderson, wrote that he “verified” that all three firearms were fired and the spent shell casings were removed after Mahdi’s execution. Anderson wrote that he also verified that there were no projectiles or fragments in the death chamber.

This is consistent with a previous statement from the Corrections Department, denying that Mahdi’s execution was botched. Department officials have said that Mahdi’s heart was located by x-ray before the execution and the independent autopsy found that two of the bullets entered through the same wound and traveled along the same path.

Mahdi was the second person to be executed by firing squad in South Carolina and the fifth to be executed since the state resumed executions in September 2024 following a 13 year pause.

Lawyers for Stanko, 54, are seeking a stay of execution from a South Carolina federal court. Stanko was sentenced to death in Horry and Georgetown counties for the murders of his girlfriend, Laura Ling, and friend, Henry Turner.

They argue that the state’s three options for execution — lethal injection, electric chair and firing squad — all violate constitutional protections against cruel and unusual punishment.

South Carolina law requires that death row defendants select the means of their own death from one of these three options. If a defendant does not choose, the default method is electrocution. Despite considerable controversy, all three methods have been found constitutionally acceptable by South Carolina courts.

Because of the state’s secrecy laws, little is known about the execution procedures other than what is revealed in court filings.

Since executions resumed in 2024, three men been executed by lethal injection while two have selected firing squad.

The death chamber inside of the Broad River Correctional Institution in Columbia, South Carolina, contains both the metal chair used in execution by firing squad, left, and the wooden electric chair, right. South Carolina Department of Corrections

The lawsuit filed by Stanko’s attorneys is the most comprehensive challenge yet to South Carolina’s methods of execution. It was filed by Charles Grose, from Greenwood, South Carolina, and Joseph Perkovich and Joseph Welling with Phillips Black, a national public interest law firm.

Stanko was forced to chose lethal injection, they contend, only in order to save himself from the electric chair, said Perkovich in statement provided to The State.

“To avoid, as one doctor has explained it, being burned at the stake by electricity, Mr. Stanko has had to choose between two methods that SCDC has shown they are unable—or unwilling—to competently conduct.” Perkovich said.

In addition to the claims about Mahdi’s “botched” execution, the attorneys say that the state Department of Corrections does not have proper procedures for determining the location of the heart, and the ammunition used by the firing squad is “inappropriate” for executions.

The attorneys also question South Carolina’s lethal injection protocol, which specifies the use of a single five gram dose of the sedative pentobarbital. Instead, the three men who died by lethal injection received a second, undisclosed five gram dose of pentobarbital, according to the lawsuit. No other state using pentobarbital, which can cause a pulmonary edema where the lungs fill with fluid, have required a second dose, according to the lawsuit.

Responding to the lawsuit, attorneys for Gov. Henry McMaster — who asked to be added as a party to the case — claim that this last minute claim that Mahdi’s execution was botched is “both factually and legally wrong.”

“While Mahdi may have ‘groaned’ two times about 45 seconds after the shots were fired, there was no report of any screaming or wailing,” attorneys for McMaster and the Department of Corrections wrote.

In addition, attorneys for McMaster, himself a strong proponent of the death penalty, argue that Stanko’s claims are moot because he fails to meet the legal requirement of offering an alternative method for his own execution that would “’significantly reduce a substantial risk of severe pain.’”

When contacted, the Department of Corrections referred The State to government’s response. A hearing on the complaint has been scheduled for later this week.

A “botched” firing squad?

Inside the South Carolina death chamber, the anonymous members of the state’s firing squad are hidden from view. They take aim through gunports in the chamber’s walls and fire.

Forensic ballistics expert Chris Coleman stated in a sworn report filed with the lawsuit that it would be “nearly impossible” for a trained marksman to miss at that close range.

“The degree of skill claimed by SCDC (South Carolina Department of Corrections) is wholly inconsistent with shots accidentally missing the target at that range and under these controlled circumstances.”

The only explanation presented by the evidence, Stanko’s attorneys argue, is that one of the three executioners did not fire their gun.

A report by forensic pathologist Dr. Terri Haddix attached to the lawsuit states that “at least three independent lines of evidence support the conclusion that only two, not three, bullets struck Mahdi.”

These are the separate paths taken by the bullets, the location of the bullet fragments and the differing damage to the paper targets that were placed over the hearts of Mahdi and Brad Sigmon, the first person in South Carolina to be executed by firing squad.

In contrast to Mahdi’s execution, Sigmon’s execution on March 7 went seamlessly. With the sudden crack of the three rifles, Sigmon, who was hooded, appeared to flinch. He made no sounds and his chest moved two or three times and then was still, reported Associated Press journalist Jeffrey Collins, who witnessed the execution.

While Collins — who witnessed both executions — reported that the target over Sigmon’s chest appeared to completely vanish on being struck with three bullets, Mahdi’s did not.

Sigmon’s autopsy showed that the three bullet wounds overlapped his heart, completely destroying it. The bullets, a type of ammunition called .308 Winchester .110 grain TAP URBAN, were so close together they appeared to make a single large path through his body and fragmented as designed. They caused enormous damage to Sigmon’s heart, left lung and a major blood vessel, along with his spine, stomach and the ribs on the back left side of his body, behind his heart.

In contrast, Mahdi’s autopsy found two separate bullet paths, hitting his liver, pancreas and left lung. Rather than completely destroying the heart, the bullets struck the heart’s lining and the right ventricle, one of the heart’s four chambers.

“With three presumed proficient riflemen firing on the targeted heart from merely 15 feet (5 yards) away in a controlled environment, using powerful hunting rifles that are capable of killing a deer at 300 to 500 yards, it would be unlikely that the left ventricle would not be obliterated three times over,” wrote Dr. Jonathan Groner, an emeritus professor of clinical surgery at the Ohio State University College of Medicine.

While an autopsy found bullet fragments spread through Sigmon’s body as far right as his liver and as far left as the ribs behind his heart, Hendrix observed that Mahdi had no fragments or injuries to the left of his entrance wounds.

It is an impossibility that two bullets could have followed the same path, Coleman wrote in his report, because the three shooters were fifteen feet, or five yards, away and firing from different angles. Therefore, all thee bullets were traveling on different trajectories.

Even if two bullets had crossed paths at the exact moment they hit Mahdi, they necessarily would have been going in different directions. As a result, they would have left pathways and fragments on the left and right side of Mahdi’s body, according to Coleman’s report.

“How bullets react once they strike the body is something that neither SCDC nor the members of the firing squad can control,” attorneys for the state wrote in the reply. “That one condemned inmate dies more quickly than another does not necessarily mean that something went awry in one execution.”

_____

©2025 The State. Visit thestate.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments