Commentary: When an unnatural heat wave kills, has Big Oil committed murder?

Published in Op Eds

Who, if anyone, is responsible when a person dies from unnatural heat? And what does the law have to say about it?

As a prosecutor for over a decade working on cases that implicated both civil and criminal liability, I have grappled with the gravity of bringing the weight of criminal law to bear in a range of contexts. Recently, along with colleagues, I have considered what implications the law has for the rising number of heat-wave deaths linked to climate change.

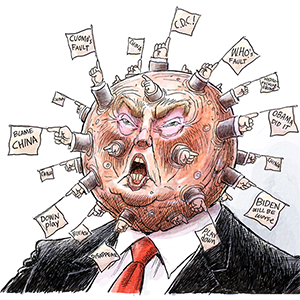

Many of the world’s recent extreme heat waves are not natural — these disasters would have been “virtually impossible” but for human-caused climate change. And a small number of oil and gas companies have emitted most of the greenhouse gases that cause climate change, while persuading the public they were doing no harm.

Civil cases are already confronting climate-change harms, some more successfully than others. One recent lawsuit filed by Multnomah County, Ore., specifically targets damaging heat waves.

And last week, the family of a Seattle woman, Julie Leon, brought the first wrongful-death suit alleging that climate heat generated by fossil fuel companies caused her death. The case alleges these companies failed to warn “the public of the dangers of the planet-warming emissions produced by their products” and “funded decades-long campaigns to obscure the scientific consensus on global warming.”

The Seattle wrongful-death case may provide a template for victims moving forward. The case also may foreshadow another court-based approach to climate accountability: criminal homicide prosecutions.

Homicide prosecutions of corporate actors are part of the nation’s — and California’s— history. If fossil fuel companies knew they were likely creating lethal climate harms, as internal documentation indicates, then homicide charges may also be an appropriate public safety response to deaths like that of Leon, given state laws that punish causing death through conduct that is reckless or that shows extreme indifference to human life.

Proving causation could be a challenge. Although it may seem odd, someone can be liable for a killing even if another person or actor was a contributing cause. Still, the complex proof here would require a combination of three facts: a public health department recording a death as “heat caused”; climate-attribution studies concluding that the occurrence of such heat would have been virtually impossible but for human-caused climate change; and proof that fossil fuel companies were the primary drivers of greenhouse gas emissions.

As a former career prosecutor, I am always concerned about the potential for criminal law to be misused. Certainly, fossil fuel corporations generate wealth and should be free to profit, even handsomely. But not when profits have a known death quotient.

A climate prosecution would not be a case of regulators telling Big Oil companies their acts were fine only to see courts unjustly punish them later. Far from an unfair bait and switch, the evidence shows the companies knew, perhaps better than anyone, that their acts were not fine but potentially very harmful, and they were able to continue to profit from that harmful conduct largely because of their own extensive disinformation campaigns. Those facts merit the moral taint the public associates with criminal wrongdoing. If that sounds extreme, so does continuing to allow reckless killing with no accountability.

Despite efforts to kill climate culpability in the courts, the public seems to favor judicial action. According to a recent poll, 62% of people across the political spectrum believe fossil fuel companies should be held legally accountable for contributions to climate change. That polling suggests society wants the law to solve problems such as unnatural heat death.

If the Seattle wrongful death-case is the first of many civil actions, what would homicide prosecutions add? Criminal and civil law offer different solutions to multifaceted problems. A proper wrongful-death suit seeks a private remedy for the aggrieved. A proper homicide prosecution — the only sort that should be brought, one that neatly checks all the legal boxes — would additionally bring a measure of public justice to the families of victims.

A homicide prosecution would also do what criminal law enforcement usually tries to do: deter similar future crimes, make the public safer, justly punish the wrongdoer and perhaps even rehabilitate the convicted by encouraging pro-climate corporate practices.

In the end, a combination of civil and criminal enforcement may be the best approach. Prosecutors should keep an eye on the new lawsuit in Seattle and think about how the facts fit the laws they enforce. A criminal prosecution of fossil fuel companies for homicide might sound puzzling at first, but if the pieces fit together to show guilt, prosecutors will have a duty to the public to consider opening cases.

_____

Cindy J. Cho is a lecturer at Indiana University Maurer School of Law. She was a trial attorney in the U.S. Department of Justice’s Consumer Protection Branch and an assistant U.S. attorney in the District of Columbia and in Indiana, where she served as chief of the Criminal Division.

_____

©2025 Los Angeles Times. Visit at latimes.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments