Editorial: NIH budget cuts are a setback for American science

Published in Op Eds

White House budgets, generally speaking, aren’t serious governing documents. Even so, they’re a declaration of national priorities — and by that measure, the latest blueprint is deeply troubling. What sort of administration aspires to shrink its budget for scientific discovery by 40%?

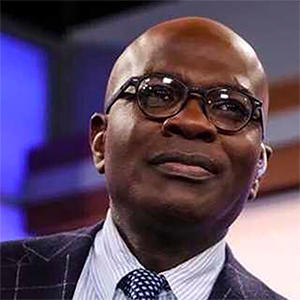

Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. recently testified before a House committee to defend cuts at the National Institutes of Health, the world’s biggest funder of biomedical and behavioral research.

The agency going forward “will focus on essential research at a more practical cost,” the secretary said. His plan would end taxpayer support for “wasteful” academic areas, including certain gender-related topics.

It’s fair for the administration to set its own research priorities. But one would expect such cuts to free up (if not increase) funding for other urgent concerns, including chronic disease. Confoundingly, Kennedy appears intent on shrinking the entire research enterprise, thereby jeopardizing the White House’s stated goals of improving public health, maintaining global leadership in science and staying ahead of China, which is set on closing the gap.

His proposal also undermines the core principle that science is a vehicle for national progress. America’s explicit commitment to support scientific research began in 1945. Inspired by wartime innovations, President Franklin D. Roosevelt asked his top science adviser to develop a program that would advance medicine, boost the economy and develop a cadre of young researchers. The resulting framework established science as a “proper concern of government” and sought to reward academic inquiry with generous public funding.

For the better part of a century, this formula worked quite well. The NIH enthusiastically funded basic research — largely through universities — and innovation bloomed. NIH grants have supported countless lifesaving advances, from cancer treatments and gene therapies to vaccines and diagnostic equipment. Almost a fifth of Nobel Prizes have been awarded to NIH scientists or grantees.

Yet several factors have sown doubt about this model in recent years. Reports that the NIH supported Chinese research on coronaviruses, a type of which caused the COVID-19 pandemic, inflamed the public and increased scrutiny over grants writ large.

Some lawmakers started to question whether the current system overwhelmingly favors established insiders to the detriment of promising junior scientists. Others raised doubts that elite universities — with their swelling administrative costs, staggering tuition rates and contentious ideological fixations — are prudent stewards of taxpayer dollars.

For these reasons, the White House isn’t wrong to scrutinize how universities spend federal money. A reassessment of the NIH’s decades-old grant framework would be salutary. The process undoubtedly would benefit from including reviewers with more diverse professional backgrounds by, say, offering stronger incentives to participate. (The tiny stipends involved hardly compensate for the work required.)

Ensuring more equitable distribution of grants among top applicants (for example, via lottery or “golden ticket” allocations) would make sense, as would more generous funding for high-risk, high-reward research.

Alas, such reforms don’t appear to be what Kennedy has in mind. Instead of limiting some costs to improve systems and expand funds for critical research, the health secretary is seeking to issue 15,000 fewer grants by next year. In so doing, he threatens to impede crucial medical studies, shrink the number of new drugs and put American scientists at a needless disadvantage — all while China lavishly invests in research facilities, improves clinical trials and streamlines regulatory approvals.

Congressional appropriations ultimately will determine what gets funded — and judging by recent hearings, lawmakers are deeply skeptical about Kennedy’s budget. By expanding support for science and encouraging careful oversight, Congress can do its part to redirect the secretary’s ambitions. It unfortunately bears emphasizing that diminishing science sends the wrong signal about America’s trajectory, to its citizens and to the world.

_____

The Editorial Board publishes the views of the editors across a range of national and global affairs.

_____

©2025 Bloomberg L.P. Visit bloomberg.com/opinion. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments