Jonathan Levin: This round of American exceptionalism is mediocre at best

Published in Op Eds

The “Sell America’” trade seems to have run its course four months after the start of an alarming and correlated selloff in U.S. stocks, bonds and the dollar. Equities have climbed back to all-time highs, and the bond and currency markets have stabilized. The signal from foreign investors is that they can’t exactly escape the world’s deepest and most liquid financial markets.

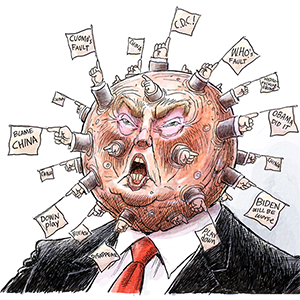

All this despite President Donald Trump’s volatile and haphazard approach to trade and immigration, attacks on the Federal Reserve and threats to the integrity of U.S. economic data, among many other things.

A lazy interpretation is that critics were simply wrong about the Trump agenda, and that his unorthodox style of governing has somehow been vindicated. But just because calamity has been avoided doesn’t mean praise is warranted.

The reality is that America’s economy is generally muddling through, expanding just enough to keep the recession fears at bay yet far from its performance the last couple of years when it was widely regarded as “the envy of the world.” Consider it a downshift from “American exceptionalism” to “American mediocrity.”

Start with the equity market. After a series of wild swings over March, April and May, the benchmark S&P 500 Index is up 9.6% for the year on a total return basis. On its face, that’s a fine performance.

But by comparison, the MSCI World Index Excluding the United States has surged 23.4%, supported by global financial, industrial and communication services companies. At this pace, American stocks would deliver their worst relative performance since 1993. And if it wasn’t for U.S. dominance in artificial intelligence, the story would be even worse: On a sector basis, only U.S. information technology companies are outperforming the rest of the world.

Some of this lagging performance is clearly self-inflicted. Although earnings have been broadly positive and defied overly-negative expectations, the momentum has wilted outside of tech and communication services.

In inflation adjusted terms, personal consumption expenditures have been essentially treading water this year, and growth in payrolls has basically stalled. And tariff rates might not ultimately end up being as high as the ones announced by Trump during the disastrous rollout of “Liberation Day” in April, but they are still poised to land at the highest in a century.

That’s complicating corporate planning, with a record 40% of chief financial officers in a joint survey by Duke University and the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond saying trade and tariff policy was their biggest concern. With employers seemingly paralyzed, it’s no wonder that consumer confidence is depressed.

Still to come: some combination of narrower profit margins or higher prices foisted on households. At the same time, Trump’s immigration policies have kept a lid on the labor force, threatening to set off worker shortages in areas such as agriculture, construction and healthcare.

The International Monetary Fund now expects the U.S. economy to grow around 1.9% in 2025, a significant slowdown from the 2.8% pace last year, even as the global economy was expected to deliver an expansion of around 3% overall. That would be the worst U.S. underperformance since 2022 and, before that, 2017.

Meanwhile, the Fed has essentially been forced into a wait-and-see stance on interest rates as policymakers guard against the threat that tariffs will keep inflation rates elevated. All else equal, that’s keeping borrowing costs higher than otherwise and helping to keep the housing sector in a deep freeze.

Trump has only made matters worse with persistent attacks on the Fed and demands that they throw inflation caution to the wind and cut rates anyway. He also fired the head of the Bureau of Labor Statistics following a disappointing July payrolls report that he baselessly claimed was “rigged,” raising concern about future politicization and integrity of data. Ultimately, longer-term bond yields and things like mortgage rates are determined by the market, not central bankers.

So if markets believe the Fed is reducing benchmark rates for political reasons — or start to worry that inflation and labor market data have become less reliable — those key borrowing costs may move higher. While U.S. borrowing costs have dropped a bit this year, they’re still about 0.94 percentage point higher on average than the typical government debt among investment-grade countries, despite signs of a weakening labor market that might have otherwise brought the spread lower. It’s hard to deny that the tariff gambit and Fed attacks have already played a role in preventing the U.S. from closing that gap in borrowing costs.

The underperformance extends to the currency market. The Bloomberg Dollar Spot Index is down about 7.9% on the year, the worst year-to-date performance since 2017 (which was, coincidentally, when Trump first took the reins of the government). It has retreated against every major currency and most in emerging markets, defying the theory that tariffs would cause the dollar to strengthen and partially offset the hit to consumer prices.

If you were an unhedged Japanese or European investor with holdings in U.S. stocks, you’d be looking at returns that were barely positive (in the case of the former) and outright losses in home currency terms (in the case of the latter.) Although the dollar’s depreciation has slowed since June, the scarring is still evident.

To be clear, this isn’t the disaster scenario in which the world suddenly and broadly turns its back on American assets. The data show that overseas flows have been largely positive since the “Liberation Day” tariff announcement that initially shocked financial markets.

In June, foreign residents purchased a net $192.3 billion of long-term U.S. securities. In bond markets, investors still understand that there’s no realistic alternative to U.S. Treasuries. Investors also still want exposure to the most innovative and dominant companies in the world.

But the outlook can certainly deteriorate as tariffs work their way through the economy, denting consumers and company profit margins, and the immigration crackdown curbs personal spending.

Even if we’re lucky and the worst doesn’t come to pass, it’s hard to still buy into “American exceptionalism.” Despite extraordinary structural advantages and exciting technological advances, the U.S. economy and financial markets are mostly just muddling through 2025. Be careful not to confuse that with vindication for bad policies.

_____

This column reflects the personal views of the author and does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Jonathan Levin is a columnist focused on US markets and economics. Previously, he worked as a Bloomberg journalist in the U.S., Brazil and Mexico. He is a CFA charterholder.

©2025 Bloomberg L.P. Visit bloomberg.com/opinion. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments