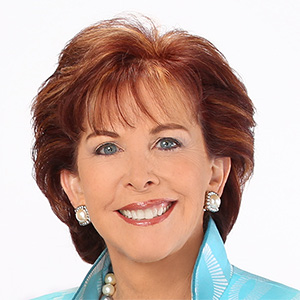

Seattle office king Martin Selig loses another piece of his empire

Published in Business News

It took more than half a century for developer Martin Selig to build one of Seattle's largest downtown office portfolios — and barely six months to lose control of most of it.

Since late last year, 19 of Selig's roughly 30 downtown buildings have been put under outside management or turned over to lenders after pandemic-related vacancies left the 88-year-old developer unable to cover more than $850 million in loans.

The latest blow arrived Wednesday when a King County court transferred nine Selig buildings to a "custodial receiver" following a default on debt of $378 million.

That came just a month after Selig lost one of his most prized assets, The Modern, a nearly new 36-story tower in Belltown, over a troubled loan of around $235 million.

Selig, once the biggest name in the Seattle office world, could still find a way to retrieve at least some of those properties. But experts say that's an uphill battle in an office market that is years from regaining its prepandemic vigor.

"I don't see how he can overcome the low occupancy issues that he's experiencing in a way that would enable him to ... bring these properties out of receivership and continue to own and operate them," said Steven Bourassa, director of the Washington Center for Real Estate Research at the University of Washington. "I just don't see that happening."

Selig has made a career of comebacks, repeatedly shrugging off bankruptcies, foreclosures and litigation by unhappy contractors.

In 1989, Selig was forced to sell his prized Columbia Center, just a few years after it opened, but earned enough from the sale to fund more projects.

Now, Selig's current list of office troubles is looking less and less like a temporary setback than the end of an era.

In March, seven other Selig office buildings — including the Second Avenue home of his headquarters — were put into receivership after defaulting on a $239 million loan. His company, Martin Selig Real Estate, also said it was cutting 86 jobs, effective April 1.

With last week's receivership court order, at least 16 Selig buildings are under outside management, while another three are in what's known as "special servicing," which typically indicates a risk of default.

Selig has also been millions of dollars in arrears over the last several years in property taxes, fees for downtown improvement districts and other bills.

All told, it's a striking reversal for a real estate pioneer who once claimed to own more than a third of the office space in downtown Seattle.

Neither Selig nor his company responded to questions.

Selig has become the octogenarian poster child for a pandemic-battered downtown office market still suffering from the persistence of remote work and lingering security concerns.

As of March, 36% of office space in the downtown area was either vacant or available to sublease, which is roughly triple the level in 2019, according to the Seattle office of Colliers, a commercial real estate brokerage.

For comparison, in the Great Recession of 2008-09, overall vacancy peaked at 22%, according to the Cushman & Wakefield brokerage.

Downtown Seattle is seeing signs of recovery. Crime is down modestly, tourists are back and office workers, though still at roughly 60% of prepandemic levels, are steadily growing in number.

But those improvements are slow, and, in the meantime, the high vacancies have cut into landlords' revenue. That's making it harder to cover mortgage payments or refinance maturing loans, especially in today's high-interest environment.

But Selig also faces other unique challenges.

Many of his buildings are vintage — the average age is around 30 years, according to county records.

Selig has done upgrades and remodels, but, generally, older offices have been harder to keep full since the pandemic and also have often earned lower rents.

Case in point: The average age of the seven Selig buildings that went into receivership in March was 37 years, according to loan documents filed with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission.

As of January, vacancy in those buildings averaged 40%, according to Trepp, a commercial real estate data firm.

That loan also shows how COVID-19 hammered the market value of office buildings.

When the loan was made, in 2014, the seven buildings were collectively appraised at around $335 million, according to loan documents.

By February, a new appraisal put the value at $150 million, according to Trepp. Yet Selig still owed $244 million on the loan, according to court filings, meaning the developer was "under water" by nearly $95 million.

Although Selig has a history of heavy debt — around $1.2 billion as of mid-2023 — he, and his lenders, could rest assured that the equity value of his office portfolio was always higher.

But in recent years, many of Selig's properties have fallen in value, which may be one reason lenders have pushed to place the properties into receivership.

Selig has other cards to play.

He has long kept a reserve of downtown properties that could be developed in the next growth cycle or, worst case, sold off to get through a downturn.

In 2018, Selig paid $44 million for a parcel overlooking Alaskan Way, across from what is now Waterfront Park — a choice asset Selig later planned to turn into a mixed-use tower, according to The Puget Sound Business Journal.

As important, Selig and his management team, including his daughter and heir-apparent Jordan Selig, were said to enjoy good relationships with their creditors.

After seven buildings went into receivership in March, the company insisted it was working with the loan servicer to "modify and extend" the loan and was "optimistic that the buildings will soon be removed from receivership," according to a statement at the time.

Many of those advantages have waned.

In early April, Jordan Selig resigned to pursue other real estate interests, a move many industry observers saw as a major blow for the company.

Selig's pull with lenders also appears to have weakened.

In April, after months of wrangling, Selig handed creditors two of the gems of his office portfolio — the remodeled former Federal Reserve building, on Second Avenue, and the brand-new 400 Westlake tower in South Lake Union — after defaulting on a $240 million loan.

Vacancy in both buildings had been above 80%. Between 2023 and 2024, their combined value had dropped from $195 million to $131 million, according to the King County assessor's office.

In May, Selig turned over the waterfront parcel, the Business Journal reported.

And for all Selig's knack for comebacks, some observers have questioned whether he can navigate his buildings out of receivership.

By the time lenders push for receivership, they've typically lost confidence in a borrower's ability to recover and are looking to sell the collateral and cut their losses, experts say.

The fact that many of Selig's properties are older and potentially harder to fill may make lenders even less willing to extend or modify loans.

"While receivership and a loan modification are not mutually exclusive, the fact that (Selig's lender) is moving to appoint a receiver likely means that there's a lower likelihood now of a potential extension (or) loan modification," said Stephen Buschbom, research director at Trepp, about Wednesday's court order for receivership.

Veterans of Seattle's commercial real estate world know better than to write off Selig.

Some recall how dramatically he bounced back after selling Columbia Center in 1989; before the year was out, he was already planning three new buildings. The sale "is not a setback," Selig, then 52, insisted. "It is a phenomenal victory."

Thirty-six years later, the consensus is that if Selig emerges from the current troubles, it will be with a vastly smaller portfolio and little financial capacity for new development.

Selig's remaining ace in the hole had been The Modern, a project initially planned as mixed-use office but repurposed as residential during the pandemic.

Over the last year or so, as Selig's troubles deepened, many observers pointed to the gleaming edifice as an attractive asset that, if sold, could help Selig stabilize other parts of his portfolio in time to ride downtown Seattle's slow but steady recovery.

But even that slim prospect vanished May 8, when The Modern was formally surrendered through what's known as a "deed in lieu of foreclosure" related to around $235 million in debt tied to the building.

It was, perhaps, a telling moment for a developer who has always kept something in the tank.

With a deed in lieu of foreclosure, borrowers avoid some of the negative effects of a formal foreclosure and forced sale, which can spook a borrower's other creditors, said Sean Holland, a former title insurance claims attorney and underwriter with experience around commercial properties in foreclosure and receivership.

But in return, Holland added, "basically, the borrower is walking away from the property with nothing."

©2025 The Seattle Times. Visit seattletimes.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments