Glaucoma-related vision loss is often preventable, but many can't afford treatment

Published in Health & Fitness

COLUMBIA, S.C. — It’s as if she’s squinting through a smoke-filled room. But it’s Charisse Brown’s eye condition, glaucoma, that diminishes her vision.

Brown, 38, has worked all her adult life, with a personal policy of keeping two jobs at once. But when she started losing sight in her left eye last year, she was forced to quit her call center job. That left her with one income stream, her marketing research job, to pay her $1,300 monthly rent and other bills.

If glaucoma is caught early, monitored by a doctor and properly treated, it’s possible to stall the progression of the disease. Eye drops are necessary for keeping eye pressure down to slow glaucoma-induced damage. Without insurance, the monthly cost of the medication can run anywhere from $80 per bottle for a generic version to $200 or $300 for a brand-name one.

As an adult without children, Brown doesn’t qualify for Medicaid in South Carolina, which has not expanded the program under the Affordable Care Act.

She’s enrolled in the lowest-premium plan on her state’s health care insurance marketplace, but ophthalmologists in the area won’t accept her insurance.

She said she called 211, a hotline for community services in South Carolina, but her voicemails weren’t returned. In medical debt and about to get kicked out of her apartment, she had to choose between her medication and paying for daily necessities like food and feminine care items. One food stamps enrollment worker told her: “We can’t approve you. If you go and have a baby, this will be a lot easier.”

“Single people — we’re struggling,” Brown said. “I feel like I’m getting punished for trying to do what’s right.”

Glaucoma is a group of eye diseases that can cause a buildup of pressure that damages the optic nerve. Long called the “thief of sight,” it’s the leading cause of blindness in Black Americans like Brown. Black people are five times more likely to have glaucoma, and lose their sight at six times the rate of white people. Hispanic and Latino communities suffer similar disparities.

Among Black patients, a timely diagnosis is paramount: Glaucoma occurs on average a decade earlier — and advances faster.

But diagnosis and treatment can be costly and out of reach for many.

In South Carolina and the other nine states that have not expanded Medicaid, opponents of expansion say it would be too expensive to provide health coverage to more people, even though the federal government picks up 90% of the tab. But forgoing expansion also has costs. People without insurance or not enough insurance are more likely to visit the emergency room, as glaucoma and other chronic diseases take their toll. When it comes to eye diseases, vision can deteriorate without coverage for preventive care. And racial health disparities are higher in states that have not expanded.

“You see a lot of end-stage disease,” said Dr. Rebecca Epstein, a glaucoma specialist and ophthalmologist at South Carolina’s Clemson Eye, which was not involved in Brown’s care. “They don’t have insurance, and so they will delay care. And then they come in, one eye is already gone, another eye is on its way — and I’m sitting here having to tell them I’ve got to operate on their only eye.”

For about two months, Brown was fully blind in her left eye. Surgeries to address her warping cornea, a condition called keratoconus, and another to relieve pressure causing her glaucoma would cost upward of $10,000. Asked if they could offer a payment plan, her doctor’s office staff said no.

For days, Brown and her siblings called dozens of charities, asking for help to pay for her surgery. They called doctors across the state, asking if they had the necessary surgeon specialists and whether they accepted her insurance. Some nonprofits told Brown she was too young, that their help was reserved for older adults.

She finally landed on the South Carolina charity Lions Vision Services, affiliated with Lions Club International. The group offers eyeglasses, vision screenings and reimbursements to local doctors for surgeries patients living below the poverty line can’t afford. The charity told her it could pay for her eye surgeries, and Brown was in disbelief.

“Access shouldn’t be this hard. Our state should do a better job of making sure that we have coverage for people and that they have access to care — before they’re blind,” Epstein said. “Here’s the crazy thing to think about: So, you don’t give them access to care. You let them go blind, and then you’re going to pay for their disability when they go blind, right? How backwards is that?”

Had she not gotten the surgeries, Brown would have lost sight completely in that left eye, doctors told her.

Before she found Lions, the search had been so frustrating that she told her mother through tears, “Maybe I should just let this eye go.”

‘Shoulder that burden’

Since Brown could no longer drive, she’d take Uber rides across town for her frequent appointments. For appointments in Charleston with her surgeon, her mother would drive from Myrtle Beach to Columbia, 2 1/2 hours away, for another two-hour drive to Charleston. After one surgery, she developed an infection and had to visit her Columbia doctor daily — $30 roundtrip — because her case was so critical. Knowing she couldn’t afford the appointments, her doctor stopped charging her at follow-ups.

Servants for Sight, a faith-based nonprofit that helps South Carolinians in poverty pay for vision care, offers to pay for surgeries, treatments and Uber rides to eye care appointments. Rideshares have helped people “not only start their care, but complete their care,” said Amy Evette, executive director of Servants for Sight.

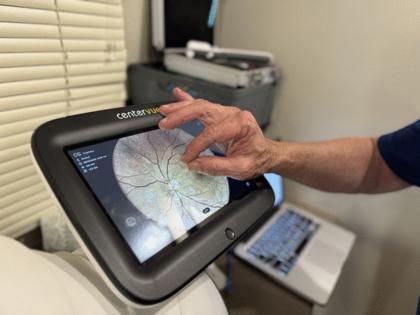

The group also runs a mobile vision screening unit that visits communities across northwestern South Carolina. Volunteers and staff screen for signs of diseases such as glaucoma and diabetic retinopathy inside the white-and-green van, and connect patients to ophthalmologists for further care. The van is equipped with retinal imaging equipment and rows of free sunglasses. On the outside are logos of various eye care centers and nonprofits who volunteer to help.

“If people don’t have insurance or are not able to afford an eye exam once a year, it’s very difficult for them to detect any kind of eye disease,” said Sandra Torres, an ophthalmic technician of 17 years. The group works with homeless shelters, and she says many people end up on the streets because they lose their sight, and then their jobs.

The vehicle saw a busy recent Thursday morning in Spartanburg, a city of about 38,000 people roughly 30 miles southeast of Greenville. Stationed in the parking lot behind a free medical clinic, staff prepared for nearly three dozen patients scheduled that day.

Multiple residents filed into the van throughout the morning, many with thick contact casts wrapped around their calves and feet, used to heal and protect diabetic ulcers. Diabetes, which increases the risk of glaucoma, disproportionately affects people with lower incomes and communities of color, amid structural barriers to affordable health care and healthier food.

Angela Garrett, a local pastor, has been grappling with blurred vision and diabetes. Uninsured, she came to the unit to get her eye pressure and vision checked. Garrett, 55, is also recovering from a recent open-heart surgery. A caregiver for older adults, she said she’ll apply for Medicaid as soon as she’s recovered and can go back to work. In South Carolina, the income limit for a single person who is blind or living with a disability is $15,650.

She’s passionate about caregiving, a pursuit “from the heart,” even though her job is “the bottom of pay in medical,” she said. Despite her modest income, she may not qualify for Medicaid.

Often, patients don’t know help is available, or they stop coming to their appointments because they can’t drive and lack transportation, or they’re unable to pay, said Dr. Peter Daniel, another ophthalmologist and glaucoma specialist who works with the nonprofits. He recalled a glaucoma patient who stopped showing up for appointments. The man began to weep when Daniel told him not to worry about the cost and connected him with the charities.

“They’re in very difficult socioeconomic and complex situations,” Daniel said. “And those are the folks that I worry about going blind.”

Columbia optometrist Dr. Kendria Cartledge sees late-diagnosed glaucoma “daily.” She said the majority of her patients are on Medicaid, and that not enough eye care providers accept the public insurance program, putting more pressure on the ones who do.

The state Medicaid eligibility redetermination process has complicated matters. Patients may have had Medicaid in the past and are still struggling financially, but as states cull the rolls, they may lose coverage without knowing it. With glaucoma patients and others at risk of losing vision, timely care gets interrupted.

“A lot of these patients are getting lost to follow-up,” said Cartledge, who has been treating whole families with the disease among multiple siblings for years, building a relationship with them. “Some expansion would definitely help out these patients have better outcomes, have a better quality of life.”

The gigantic tax and spending bill the U.S. House approved could make that situation worse. The measure would cut federal Medicaid spending by $625 billion over 10 years, largely by enacting new work rules and additional paperwork requirements. The changes would remove about 7.6 million people from the Medicaid rolls over the next decade, according to initial estimates by the Congressional Budget Office.

Ophthalmologists like Daniel give care knowing they’re losing money, even after partial reimbursement from charities.

“If a charity can carry that burden, why can’t our state and federal systems help shoulder that burden? We do it for older patients, we do it for our Medicare population,” said Epstein, the Clemson Eye ophthalmologist. “Why can’t we do it for our younger patients?”

When ‘all else fails’

Clad in a bright yellow tunic and woven sun hat, Jekeithlyn Ross stopped by the Servants for Sight check-in table to introduce herself. Only she didn’t have to. Marion Keller already knew Ross was the daughter of eye disease advocate J.C. Stroble as soon as she spoke her dad’s name. Keller has a bobblehead figurine of Stroble in her curio cabinet.

Ross has been on a mission to relaunch her nonprofit, the J.C. Stroble Glaucoma Awareness Foundation. Dormant during COVID-19, the organization is named for her late dad, who had glaucoma and was blind. The eye care advocate and Spartanburg icon died in 2013 at 71.

“Trying to get services to those that are falling between the cracks or the socioeconomically challenged is a challenge,” Ross said. “What we’re trying to do is go to the people, try to get the services to decrease the rate of blindness here.”

A volunteer with the South Carolina Lions Club and speaker at churches and national and local civic events, Stroble was also well-known in the community for his boisterous order-calling at the local fast-food fixture, the Beacon Drive-In. The eatery, where he was nicknamed the “Beacon Barker,” is popular among locals and as a stop on campaign trails. Inside, Stroble’s portrait adorns the wall chronicling the diner’s storied history, which includes presidential candidate visits, along with benchmarks like the launch of the internet.

At the Servants for Sight check-in table, the excitement was palpable: Ross and Keller talked about their mirrored missions as if they were old friends. Keller shared that she had a cornea transplant, and before they parted ways, she and Ross blew each other a kiss. “This is a marriage. This is only the beginning,” Ross said.

Ross said she was aware of glaucoma because of her dad, but others without exposure might not know the importance of getting their eyes checked, or even that it runs in their families.

“We’re back in action — because the need is great,” Ross said. “Education, awareness is the key. It’s essential, and it’s not enough foot soldiers out there putting that message out.”

She’s been going to churches, civic groups, clinics and mobile units to spread the word about the foundation.

“Nonprofits pick up the pieces. We have a little joke: ‘When the government and all else fails, then you come to us,’” she said with a wry chuckle. “Because what do you do? You help.”

‘Like looking through a plastic sandwich bag’

Servants for Sight helped pay for glaucoma surgery and eye drops for 71-year-old Jimmie “Coach Sheek” Robinson. The retired school bus driver and Little League coach said he’s had trouble accessing Medicare.

“It was like looking through a plastic sandwich bag,” he recalled. “I’m asking, ‘Lord, what is happening to my eyes?’”

Often running in families, glaucoma can sneak up in those with 20/20 vision all their life, like Robinson.

He couldn’t see his fellow churchgoers’ hands, extended to greet him with a handshake. He’d have to explain that his peripheral vision was waning.

Handshakes matter at Piney Grove Baptist, a small congregation with scarlet carpets in Anderson, about 30 miles southwest of Greenville. A “flimsy grip won’t do it,” said one deaconess at the podium on a recent Sunday. “You can tell someone loves you,” she said, by their handshake.

“Shake my hand,” she exclaimed as parishioners laughed. “Show up with love.”

That day, Robinson, donning glasses, was able to do that. Throughout the sermon, he’d wave his hand in prayer over his daughter and grandchildren, who filled the pew behind him.

“I’m not going to get depressed over my eye,” he said. “God been good to me.”

Back in Columbia, with those costly prescriptions, doctor and rideshare visit costs adding up, Charisse Brown said she is now steeped in about $7,500 in debt, with Uber costs totaling $1,500 alone. She’s kept a GoFundMe up to try to chip away at bills through donations.

She has just moved into another apartment, a gray-floored two-bedroom, where rent is $300 cheaper than her previous one-bedroom flat. Leaving lights on at night, along with the beaming lamppost right outside her back door, helps her navigate her apartment after dark.

“That’s pretty much the only way that I am able to see, is enough light is coming in, especially in my left eye,” she said.

Brown said her friends have noticed her own light dimming.

Friends have always called her “Kumbaya” for her outgoing and positive attitude. But after her vision crisis, she fell into despair. She stopped going out, self-conscious about the appearance of her left eye, which is sometimes swollen and has strabismus. Because she can’t hop in her car for a spontaneous road trip like she used to, she’s leaned on her personal avatar in the online game “Second Life,” where she simulates going to the beach and streams her pastor’s sermons, as if she’s sitting in the pews.

She’s trying to lift her spirits by writing poetry and tending to her plants. In the corner of her sparsely furnished living room sits a fern she’s named Duchess, a pothos called Prince and a few other small pots, studded with budding succulents.

Sitting on the couch, she reads from her poem “Overcome.” She’d been lying in the hospital bed after a surgery, using speech-to-text to write:

Darkness and light both dwell in the same universe, but light always outshines – so I nicknamed myself ‘Bright,’

To be able to blind the Dark from coming my way.

It’s so blinding that maybe he would give up

And leave me alone today.

____

This story is part of “Uninsured in America,” a project led by Public Health Watch that focuses on life in America’s health coverage gap and the 10 states that haven’t expanded Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act.

____

Stateline reporter Nada Hassanein can be reached at nhassanein@stateline.org.

©2025 States Newsroom. Visit at stateline.org. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments