Worried about political violence, some lawmakers want to scrub home addresses

Published in Political News

WASHINGTON — As members of Congress debate how best to protect themselves following the murder of a Minnesota state legislator and her husband, privacy advocates are sounding a note of caution against piecemeal responses, while also urging broader legislation for all Americans.

According to court documents, the alleged shooter, who compiled a long list of Democratic politicians to target, may have found his victims’ addresses online through data brokers. Now one of the Democrats named in his writings, Sen. Amy Klobuchar of Minnesota, wants to make it easier for lawmakers to scrub their personal info from the web, akin to a law enacted in 2022 for the federal judiciary.

“This murderer, he went to the addresses that he knew. He had some names without addresses; he didn’t go there,” Klobuchar said at a press conference last week. “Sen. Cruz and I have long advocated for some changes. I believe we have growing support for that.”

In the last Congress, Klobuchar joined with Sen. Ted Cruz, R-Texas, on an amendment to the National Defense Authorization Act that would have covered members of Congress and their families, along with any congressional employee who’s been the target of a threat. It would have let those “at-risk individuals” ask government agencies to remove the addresses of their residences (including secondary residences), personal email addresses, home and mobile phone numbers, and other information from publicly available content, and would have prohibited data brokers from selling their information.

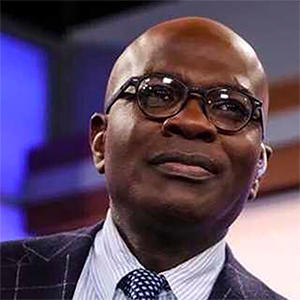

For Daniel Schuman, executive director of the American Governance Institute, a proposal like that one is simultaneously too broad, too narrow, and besides the point.

As written, it could potentially be used to squelch all sorts of legitimate speech, Schuman said. While there is an exception for any “commercial entity … engaging in reporting, news-gathering, speaking, or other activities intended to inform the public on matters of public interest or public concern,” he wonders if that would include someone like him, who writes a weekly newsletter, or other organizations that blur the traditional lines between advocacy and journalism.

In theory, it could also let lawmakers hide politically damaging information from the public. A lawmaker’s home address usually isn’t newsworthy — unless it’s an apartment owned by a lobbyist. The proposal covers the “routes taken to or from an employment location,” which an overzealous official could argue includes providing directions to where a lawmaker is giving a speech, Schuman said.

It’s also unfair that politicians would get more power to control their information than the rest of us, Schuman said. There are already ways anyone can scrub information from the internet, which he’d like to see made easier.

The Electronic Frontier Foundation, a digital privacy group, echoed that criticism.

“Lawmaker fears are understandable these days, but publicly available information about prominent officials can be an important source of accountability. Overall, privacy protections should be for everyone, not just a chosen few,” said EFF Legal Director Corynne McSherry in an emailed statement. “We need comprehensive privacy legislation that protects all Americans while preserving First Amendment rights. Congress should be focused on protecting all of us, not just itself.”

The EFF noted that Congress has, in the past, enacted broad protections in response to a prominent figure having their privacy invaded. After a reporter published a copy of Judge Robert Bork’s video rental history during his Supreme Court confirmation hearings, Congress made disclosing someone’s rental or sales history of audio-visual materials illegal — whether they were a public figure or not.

But even if Congress narrowly tailored a proposal to account for information the public deserves to see, and widened it to cover everyone, Schuman doubts it would solve the problem it sets out to fix. Politicians are easy people to find, and making it harder — not impossible — to find a home address is not a guarantee against violence. After all, Gabby Giffords wasn’t shot at home, nor was Steve Scalise.

“This is driven by fear, and the danger arises from a violent culture that’s stoked by members of Congress that are using language that prompt crazy people to do crazy things, and by the easy access to weaponry,” said Schuman. “Are we really going after the root cause?”

Cruz’s office did not respond to requests for comment. Klobuchar’s office declined to comment, but did point to public statements she made in support of reviving the proposal. The pair worked on another bill, signed into law earlier this year by President Donald Trump, that prohibits the nonconsensual publication of sexual images online, whether real or computer-generated.

Meanwhile, other lawmakers have responded to the Minnesota slayings by pushing for more comprehensive privacy protections. Rep. Lori Trahan, D-Mass., told The Washington Post she would continue efforts to pass a proposal she reintroduced in April alongside Sens. Bill Cassidy, R-La., and Jon Ossoff, D-Ga., that would let Americans use a centralized online tool to ask to delete their information from registered data brokers. Sen. Ron Wyden, D-Ore., similarly told Wired he would pursue more regulations on data brokers.

Threats against members of Congress, their families and staff have risen dramatically in the past decade or so, with the Capitol Police reporting 9,474 “concerning statements and direct threats” in 2024.

In the wake of the Minnesota shootings, some lawmakers called for a boost to Members’ Representational Allowance funds, which cover office expenses in the House, and more leniency to use MRA dollars to cover private security services. Others want to see more assistant U.S. attorneys assigned to investigating and prosecuting threats.

Many lawmakers have yet to take advantage of a program providing them with $10,000 to install residential security equipment and another $150 per month to cover operating costs.

_____

©2025 CQ-Roll Call, Inc., All Rights Reserved. Visit cqrollcall.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments